The stark reality for the construction industry is that many construction businesses are entering different types of external administration. Whether it’s administrators, receivers or liquidators – construction companies are unfortunately suffering the effects of complex economic conditions over the last few years.

But the woes don’t necessarily stop when a company goes into liquidation. Beyond the obvious resourcing issues, remobilisation costs and unpaid invoices come a series of powers that are unique to liquidators.

For today, we are focusing on just one: the ability to claw back an “unfair preference” from someone who has been paid money by the company in liquidation.

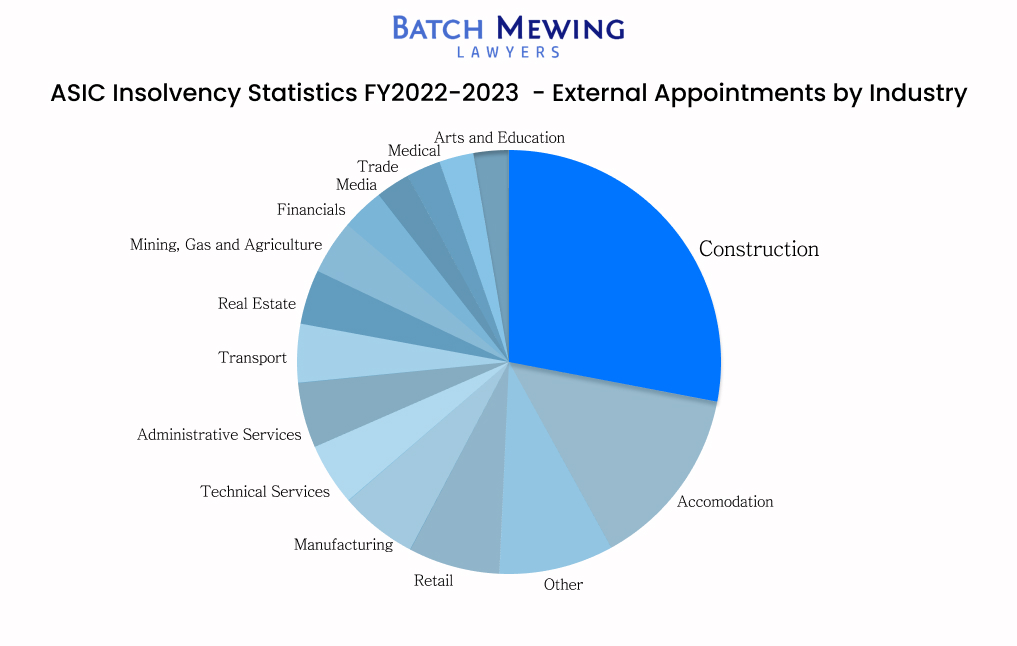

And if a liquidator of a former (now insolvent) debtor hasn’t attempted to claw back and “unfair preference” yet, they probably will at some point. After all, insolvency in the construction industry remains a major percentage of overall insolvencies around Australia:

The Basics of an Unfair Preference

In a nutshell:

- You issue an invoice to a company;

- It pays that invoice;

- It then goes into liquidation a few weeks later;

- The liquidator writes to you asking for the money back as an “unfair preference”.

Automatically, most people’s reaction is to say “that’s unfair!”.

After all, why should you have to hand back your hard earned payment?

The system here is designed to try and make it fair to all the other people who didn’t get paid. So, while (usually after some effort) you got your invoices covered, there are typically others who didn’t. While that’s not your fault necessarily, the rules are designed to try and make it fairer for the creditors generally, not just specific creditors.

And as we’ll see, the liquidator can’t just demand payments back willy nilly. They do, in fact, have to demonstrate some key elements before you should be actually concerned about a preference claim.

Threshold Question 1 – Timing

A liquidator can’t reach back to the beginning of time to claw back payments that were made by the company.

To be claimed as an unfair preference the payment generally has to have been made within 6 months before the liquidation commenced.

When the liquidation “commenced” is usually when the appointment was made, though there are a few twists and turns that could nudge that around a bit.

Threshold Question 2 – Insolvency

To be an unfair preference, the payment needs to have:

- Been made when the company was already insolvent; or

- Caused the company to become insolvent.

There is a range of standard practice when it comes to demonstrating a company was insolvent at the time of a transaction.

To understand that, we need to appreciate the commercial context in which a liquidator is likely to be writing to you, attempting to claw back a payment you received months prior from a company now in liquidation.

A liquidator’s job, of course, is to collect in the companies assets, turn them into money, and distribute what’s left (after costs etc) to the creditors.

Often, a liquidator will kick that process off by:

- Issuing demands for debts owed to the company; and

- Auctioning off the company’s physical assets where possible.

As this goes on, the liquidators might soon after that turn their minds to potential unfair preference claims.

That will involve:

- Forming something of a view about when the company became insolvent (put simply, unable to pay its debts as and when they fell due);

- Finding out what payments out were made in that time;

- Taking an initial assessment about which of those might be vulnerable to a preference claim.

So it’s pretty common for you to receive a letter about preference claims before the liquidator has a total or complete understanding of the company’s history.

As a result, the demand you receive from a liquidator might:

- Simply assert the company was insolvent when it paid, without further explanation;

- Contain some more facts and figures to develop an argument of insolvency; or

- Rarely, but possibly, contain a full insolvency report.

Determining insolvency is sometimes a complex question, so a demand without a compelling case of insolvency behind it is inevitably open to some debate.

That said, the strength of a conclusion about insolvency depends entirely on the facts so it’s a case by case assessment whether this might give you some ability to push back on a demand.

Threshold Question 3 – Received More

The liquidator needs to show that you received more by being paid than you would if you had to participate in the winding up process as a creditor.

Almost inevitably this is true, because the returns you are likely to receive in a liquidation are often much lower percentages of what was owed.

Other Questions to Ask

So, you’ve received a demand and it seems (on its face at least) to tick the boxes we’ve set out above.

As a result – you’re concerned that there could be a claim against you.

What are some other areas you might consider?

1 – Were you Secured?

An unfair preference claim only arises in relation to unsecured debts.

So, if you had a security in place you might have some ability to push back.

However, that will only generally work if your security had some value, so if you were the 27th ranking security holding in a company with only a pack of matches to its name, then this might not assist.

2 – Were you Aware?

There is a defence available to unfair preference claims which I like to call the “total ignorance defence”.

Basically if you can demonstrate that you had no knowledge the company was in financial distress, and a reasonable person in your position would not have had any such knowledge (at the time the payment was made) then you might be able to establish this defence.

This, of course, creates a tense irony. The businesses with more robust followup and collection activities on their invoices are, in fact, more likely to reasonably suspect when a company is in financial distress. As a result their diligent and effective collection practices actually work against them here.

3 – Funding

Before being particularly concerned about getting sued by a liquidator, it’s always worth trying to get your hands on their latest report (either to creditors or submitted to ASIC if available) to see what they have in terms of cash on hand.

Getting into a big contested piece of litigation isn’t that cheap. So if you can see that the liquidators lack any means, that’s at least worth factoring in to what response you send.

Of course, liquidators can sometimes find lawyers to act for them without payment, on a “no win no fee” basis, if their case is strong, so this is just a factor to consider not something that you should bet the house on.

Received a Demand for an Unfair Preference?

If it hasn’t happened yet it probably will at some point.

The above is a high level summary of a fairly complex area of law.

As a result, if you receive a letter from a liquidator your best bet is to get some legal advice on it as soon as you can. That way your lawyers can dig into those factors above (and some others) a bit more and give you guided advice on the specific circumstances you are in.